Do You Know How Much Your Business Is Worth?

If you own or manage a midsize company, do you have a firm understanding of its value? Right now, at this moment? Do you know with certainty how much value you created in the past year? Can you pinpoint where in your business value is being created and where it’s declining?

If the answer to any of these questions is “no,” you could be putting the future of your company at serious risk.

Recently, one of us (Reed) advised a family-owned company that operated three distinct business units, each in a different industry. Two of the units were doing well in promising industries while the third was lagging in a declining industry where valuations were at an all-time low and unlikely to rebound. Unfortunately, instead of devoting the bulk of their time and energy to making the well-performing businesses better, management had been consumed with trying to fix the struggling business.

The damage wrought by this approach became obvious only when the company was sold. Because the three business units were in different industries, the sale involved three separate buyers. The high-performing businesses fetched about $75 million each. The struggling business — the recipient of so much of their attention — reaped only $12.5 million.

Imagine what the value of the combined company could have been if management focused their efforts on the businesses worth improving by investing in creative talent and innovations, expanding the customer base, fine-tuning quality, and the like. In a few years, a targeted growth strategy might have enhanced those already promising businesses to the point that buyers were willing to pay a 25% premium, or $100 million each, instead of $75 million. Even if those investments required closing the third business down, the combined $50 million boost in market value would have more than compensated for the costs of shutting down a bad business.

While any company can make errors of this nature, family businesses may be at increased risk. Their rich histories and traditions (which are usually among their strongest assets) can become liabilities if emotional attachments cause leaders to hang on too long or resist embracing new directions. For such companies, clear, objective valuations offer essential reality checks.

Unfortunately, most owners and managers of midsize, privately held companies (family-owned and otherwise) operate from day to day with no clear understanding of their value. That’s because busy executives often assume there is no easy way for them to determine value and simply put the subject aside. Unlike their publicly traded counterparts, they don’t have the benefit of automatic, daily valuation based on stock price, nor do they have teams of corporate strategy executives standing by to analyze value creation. Many leaders of midsize companies also see third-party valuations as complicated, time consuming, intrusive, and expensive. Thus, they undergo them only when they must — for example, when seeking capital for growth.

Despite these challenges, if you own or manage a midsize firm, it’s imperative that you conduct a detailed valuation at least once a year. Think of it as you would your annual physical — an essential step to find out what is going right, and more importantly, what may be going wrong. Then, you can take corrective action before it’s too late. You could avoid spending precious resources courting the wrong customers, trying to grow areas of your business that are inevitably declining, and failing to recognize and invest in your areas of greatest opportunity. Plus, if you’re approached by a buyer interested in acquiring your company, you’ll be prepared to respond and negotiate. Instead of fishing for some hazy “X times EBITDA” figure you overheard at your last industry conference, you’ll have a clear idea of what your company — not just those like yours — is worth, and why.

A More Accessible Valuation Method

To make the valuation exercise easier and more approachable, we created a new methodology called QuickValue. It’s based on Reed’s experience working directly with hundreds of middle-market leaders, helping them better understand what their companies are worth, and why. To perform this kind of self-guided valuation, your internal team doesn’t need future financial projections — most of what you need is at hand, and what you don’t have can be obtained easily. Your company’s executives know the business better than any consultant ever will, and they won’t need to bring anyone up the learning curve.

Our approach to this exercise emphasizes a close analysis of your firm’s most important value drivers: those characteristics of your business that make it unique. Even companies in the same industry and with similar metrics may vary widely on everything from the quality of their leadership to pricing power to brand equity. Thus, a careful, thorough, and honest appraisal of these value drivers is essential to calculating an individual company’s value.

First, you’ll identify the most important value drivers to your business — we suggest picking eight to 12 — and then rate each on a score of zero to 10, with 10 being best to create your Value Driver Score. This score forms an important element in of your valuation, because it quantifies the qualitative aspects of your business which most other valuation methods ignore. Then, you and your team use market-rate multiples of public companies to assess the value of businesses similar to yours. Finally, if you are a privately owned midsize company, you’ll need to adjust for the lower multiples (typically 25-30% lower) of M&A transactions involving private companies.

The next step involves bringing it all together. While gaining the three crucial pieces of data — your assessment of your value drivers, your EBITDA multiple, and your adjusted EBITDA — takes some serious work, after that, a fairly simple calculation yields the number you’re after: a clear, well-supported value for your business.

This valuation process will enable you to:

- Avoid selling your business at a discount to its true value.

- Better focus on how to improve your company by enhancing your value drivers.

- Create a strategic plan that has value creation as the centerpiece.

- Incentivize your staff based on the value they create rather than using revenue or EBITDA targets.

How to Know What You’re Worth

Consider the following hypothetical example. Company X is approached by a competitor with an acquisition offer. The price, the competitor says, will be based on a widely used industry multiple of 12x EBITDA. The two companies are in a fast-growing industry, and both are performing well.

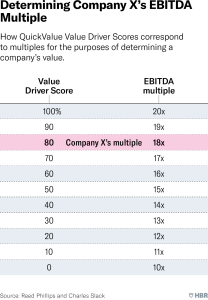

Fortunately, Company X’s managers have recently completed a self-assessment of their firm’s value, and believe they have a strong, defensible case for valuing their company at 18x EBITDA, not 12.

How did they get there? An internal team of four senior executives covering core disciplines — finance, product, marketing and manufacturing — worked together, debating which value drivers were most important. Dispensing with drivers that didn’t apply to their software business, such as supply chain and franchiser-franchisee relationships, the team determined that areas such as intellectual property, leadership, and pricing power mattered most to their development and success.

Then, they rated themselves on each driver using a zero-to-10 scale with extra emphasis placed on drivers they deemed especially important. It was a spirited, frank, and revealing conversation. They took care to judge themselves thoroughly, including both the drivers where they excelled and the inevitable ones where they needed to improve. They tallied these ratings up to arrive at their overall score of 112 out of a possible 140 points. Even though the team rated just 10 value drivers, one was deemed critical and received triple weighting (30 possible points), two were pegged as very important and received double weighting (20 points), and the remaining seven had a regular weighting of 10 points. Using our system, they got a Value Driver Score of 80% (112 points divided by 140) — a very high score only awarded to the best companies.

Next, they examined the EBITDA multiples of 15 public companies in Company X’s industry. (In this case, an investment banker they knew provided this information, though there are a number of ways to gather it quickly.) This allowed them to develop a valuation range, which they then modified slightly downward to account for the difference between public and private company M&A multiples. The range, which was 10x–20x EBITDA, is where Company X would find its value once it applied its score. The company’s strong score puts it at the high end of the EBITDA range, at 18x, as you can see in the table below.

If Company X had been acquired for the price its competitor offered, it would have been a bargain for the buyer. That’s because companies that sell for 12x EBITDA have much lower scores.

By not accepting the offer, Company X dodged a bullet. Its $10 million in EBITDA makes the company worth $180 million (18x EBITDA), which is $60 million more than what was offered.

It must be noted that the hypothetical story above highlights a best-case scenario. Not every company warrants such a laudable score, and we used the word “defensible” for a reason. Self-assessments that are exaggerated will be discovered quickly by any buyer during due diligence. More important, self-deception is counterproductive to the very idea of this exercise, because you won’t come away with information you can build upon. If an honest appraisal yields a low value for your business, that’s disappointing, for sure. But it’s priceless information that you can use moving forward to make your company stronger.

About the Authors

Reed Phillips is the CEO and cofounder of Oaklins DeSilva+Phillips, the M&A specialist firm in media, marketing, information, and technology. Based in NYC, Reed has been an investment banker for over 30 years, during which time he has completed over 225 M&A transactions.

Charles Slack is an award-winning business writer and editor and the author of several books, including Liberty’s First Crisis and Hetty: The Genius and Madness of America’s First Female Tycoon.